Project Details

CARNTON

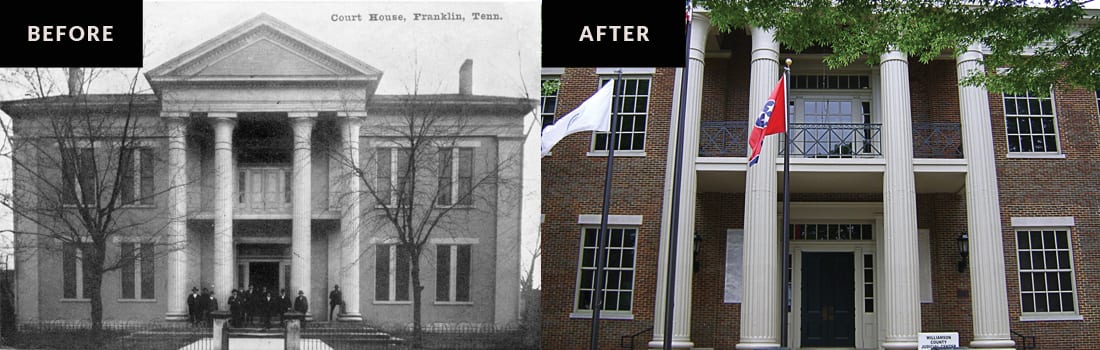

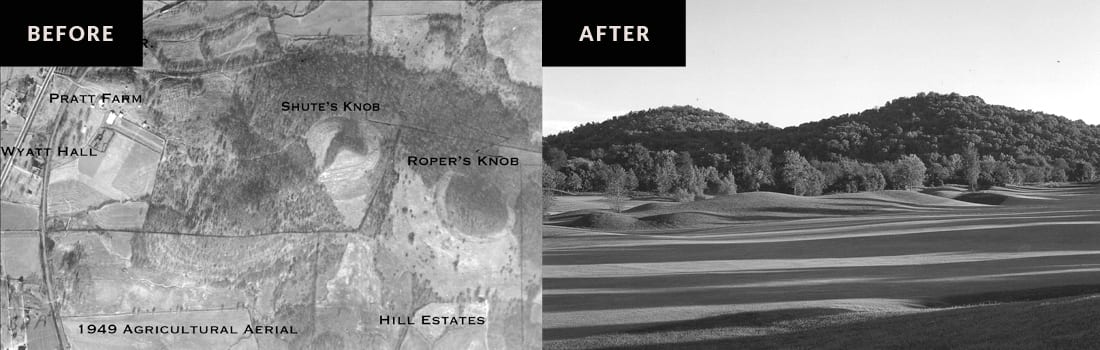

Imagine Franklin without a Carnton. No house museum for out-of-town guests to visit. No weddings in the garden. No The Widow of the South. No school children on field trips. No summer concert series on the lawn. Who would know the name Carrie McGavock? What would surround the Confederate cemetery? How much poorer would our community be without one of its crown jewels?

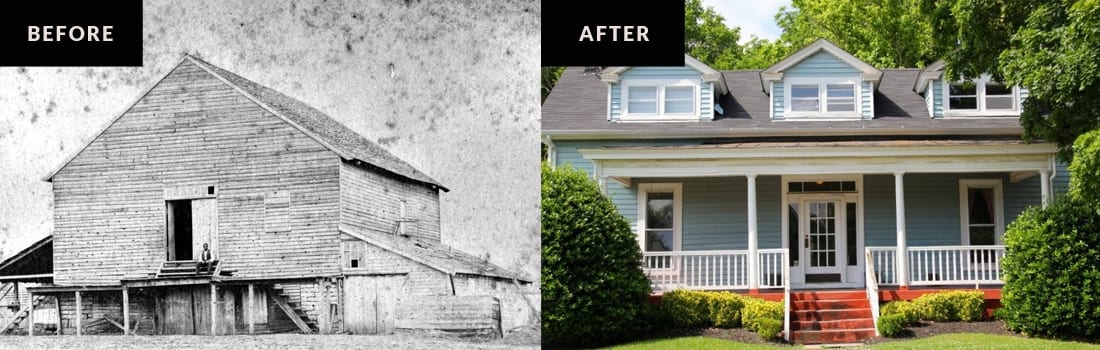

Built in 1826 by Randal McGavock, the house that served as the largest Confederate field hospital following the Battle of Franklin was sold out of the McGavock family in 1911. Over the next sixty years the house slid slowly and more deeply into decline, frequently owned by absentee landlords and leased by tenant farmers. At one point the doors to the building were missing and motorcycle parts were stored in the third floor attic. Animals wandered freely through the first floor and the blood stains on the second floor were buried under bales of hay. It became something of a rite of passage for high schoolers to attempt to spend the night in the rumored-to-be-haunted building.

But the times they were a’changing. In 1967 a small group of determined Franklinites committed themselves to saving Franklin’s landmark structures before they fell to the bulldozers of progress. They called themselves the Heritage Foundation of Franklin and Williamson County. One of their early goals was to save Carnton before the grande dame succumbed to age and neglect.

Franklin had already experienced one charity ball, given the previous year by Ruth Anne and Mark Garrett. The Garretts threw a party every year, but in 1972 they asked their guests to make a $25 per person contribution to the newly-formed Heritage Foundation, of which Mark was an early president. The next year, 1973, he asked Marty Parish Ligon to throw the gala on behalf of the Heritage Foundation. “I said I would do it if we could save Carnton,” she remembered.

A spitfire ball of energy, Ligon threw all her efforts into transforming Carnton from what it was then to what it could be. She had one very important guest in mind: Dr. W.D. Sugg of Bradenton, FL, who owned the home and 165 acres surrounding it. Dr. Sugg had grown up near Franklin and attended Battle Ground Academy. Although he did not have a family connection to Carnton he had purchased the property a few years earlier and had expressed an interest in someday restoring the home and retiring there. But to some in Franklin that reality seemed a long way off, and every year the house seemed to slip a little closer to the point of being past saving. Ligon wanted Dr. Sugg to see a Carnton restored from the neglected home of a tenant farmer to a historic jewel with both a profound history and a promising future. She would throw the first gala at Carnton since before the Civil War, more than a hundred years earlier. And she would do it in just three months.“I didn’t have time to assemble committees and get lots of input,” said Ligon. “I just gave different people jobs and told them to do it.”

One of those jobs fell to Ann Herbert Floyd.

“I told her it was her job to find as many pieces that were original to Carnton as she could and to bring them back home. She was absolutely magnificent.”

As it happened, Floyd’s then-husband, Wilson Herbert, was related by marriage to a McGavock descendant who lived in North Carolina. Floyd called the relative and asked if they had any artifacts that might be original to the home.They did.

Did she by any chance know any other descendants who might have artifacts?

She did.

Would they be interested in attending the Heritage Ball, and bringing some of their artifacts to loan to the home for the evening?

They would.

In the end, Ligon and Floyd rounded up McGavock descendants from North Carolina, Texas, Alabama, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

Floyd had another card up her sleeve. Harriet Bartlett, a McGavock descendant who lived in Franklin, had hosted a bridal shower at her home some years earlier and Floyd had been a guest at that shower. Floyd remembered walking in to a modest home and seeing an enormous portrait hanging over the mantel. When she inquired as to the subject of the painting she learned it was one of Harriet’s ancestor’s from Carnton, one Carrie McGavock.

“All I could think about was that gorgeous old portrait hanging over Harriet’s fireplace. I knew we had to get it to the ball. As it turns out she was delighted that we were interested in her ancestor.”

Floyd found other portraits, too, and other artifacts: Carrie’s finger bowls, silverware, cruet service, book of scripture excerpts, and black silk stole; leather-bound books inscribed with the McGavock name and containing Andrew Jackson’s signature; a china cigar holder and humidor; a cameo necklace, gold bracelets, silver pitcher and mother-of-pearl calling card case that belonged to Randal McGavock’s wife Sarah; a doll chair and cradle. Also among the artifacts was Carrie McGavock’s cemetery book, her guide to the locations of the final resting places of the 1,484 soldiers interred in the Confederate cemetery.While the old home served as inspiration for the evening, it posed a huge challenge, too. It was in poor condition and not exactly “company ready,” although it was being lived in by the Robersons, the resident tenant farmers. Ligon was undaunted.

“We moved the Robersons into the Holiday Inn for a little more than a week and took over the house,” she recalled. “We hung a chandelier in the center hallway. The electrician called to tell me that the wiring wouldn’t support the chandelier, and I told him to just rewire whatever he had to in order to make it work. There were some leaks we had to repair. We repainted the downstairs. We brought in oriental rugs to cover the floors.”

Floyd took over what is now known as the best parlor to display the collection of McGavock family artifacts. She borrowed glass display cases from some of the local stores.

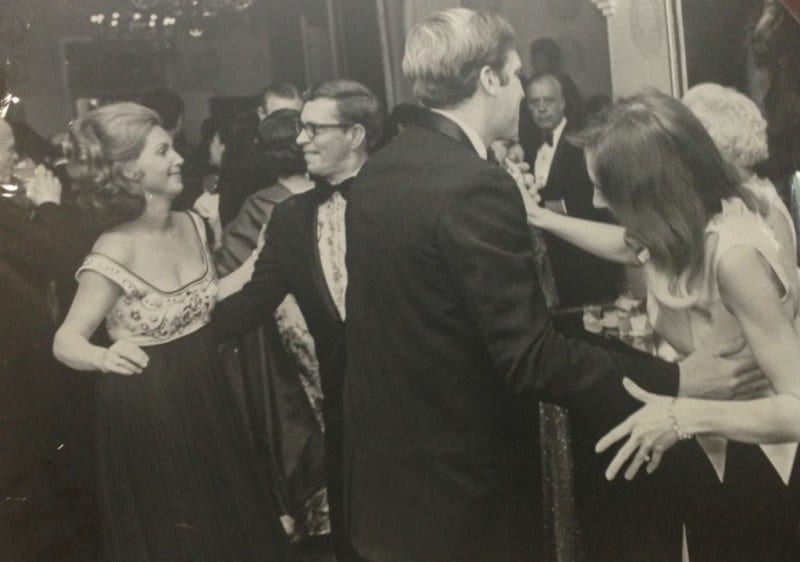

By the time the walls had been painted, the carpets laid and the display cases installed, “We had that room looking right nice,” remembered Floyd.When the big day arrived Carnton had been spit shined and polished better than she had been in years. Ball goers arrived at the back of the house, where visitors currently enter the home, and made their way onto the porch where those generals who were killed during the Battle of Franklin received their final respect. Guests then entered the home and viewed a glittering jewelry collection from Neiman Marcus in Dallas and the collection of McGavock family portraits and artifacts before making their way out the front door to a tented front yard where dinner and dancing awaited. The design committee had settled on a theme of dried flowers and grasses in keeping with the antebellum setting and September date, and the Town and Country Garden Club had spent all summer cutting wildflowers from beside local roadways, drying them in Sandy Zeigler’s barn, and arranging the foliage. Tables were set for some 700 guests and two orchestras were ready to entertain until 2 a.m. Dinner, at 10 p.m., consisted of a plantation breakfast: country ham, chicken breasts simmered in wine, hot biscuits, grits and fruit.

Ligon and her team of outstanding volunteers had done their job and now it was up to Dr. Joe Willoughby to close the sale.

“I knew I wasn’t the one to talk business,” said Ligon. “I told Dr. Willoughby, ‘I want you to convince Dr. Sugg that we need to save Carnton.’”

While the Heritage Foundation gladly would have accepted the donation of the home, its interest was in preserving Carnton for future generations, no matter what the ownership structure. Dr. Sugg had at one point considered leaving Carnton to the State of Tennessee after his death, but Dr. Willoughby, Richard Jordan, Joe Pinkerton and Curtis Green ultimately convinced him it would be better to establish a new non-profit corporation, the Carnton Association, and to donate the house and ten acres to that entity, which would own the home and be responsible for its restoration and preservation. At the Heritage Ball in 1977 Dr. Willoughby read a telegram from Dr. Sugg announcing that the conveyance had taken place.“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has,” Margaret Mead said.

Thanks to the efforts of a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens 40 years ago and the generosity of Dr. Sugg, today Carnton hosts some 50,000 visitors a year, visitors who come from every corner of the globe and who take home an understanding of and respect for the piece of the Civil War that played out in our own backyards.

And over 40 years after the Heritage Ball that showed Carnton as the diamond in the rough that she was, the Heritage Ball is still supporting the mission of the Heritage Foundation: protecting and preserving the architectural, geographic and cultural heritage of Franklin and Williamson County.