History of Williamson County’s Last Remaining Rosenwald School

NATIONAL TREASURES, COMMUNITY RESOURCES: REVIVAL AND RESTORATION OF THE LEE-BUCKNER ROSENWALD SCHOOL

Blake Wintory, Ph.D. Director of Preservation

Rachael Finch, Preservation Consultant

“It’s like coming home and seeing where you used to live…it’s my history.”

Mrs. Georgia Harris, alumnae of Lee-Buckner Rosenwald School [1]

(Lee-Buckner Rosenwald School, August 2020. Image courtesy of the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County)

If you drive the many backroads of the South, you may come across an unusual structure at least 100 years old. You might mistake it for an old, abandoned home. One side of the structure would have a large “battery of windows”[2] (boarded up or missing) while the other side would have had smaller ones. The structure would be in poor condition or virtually falling down. These structures seem ghost like, deserted and derelict. However, their walls hold stories of resilience and perseverance, representing the essence of a community’s identity. These structures are Rosenwald schools.

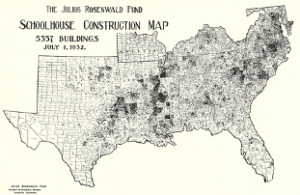

Prior to the creation of Rosenwald schools, many African American children sought education inside of churches and barns, without proper supplies, and at times, without teachers. In collaborative spirit, Booker T. Washington, founder and president of Tuskegee Institute and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears, Roebuck & Co., formed a unique partnership and engaged in a radical experiment to bridge the educational divide by building these schools to help support educational equality for African American children in the southern United States. Rosenwald schools modeled progressive theory and practice, provided sanctuary, and secured instructional opportunities. Between 1912-1932, thousands of schools, financed in cooperation by communities and the Rosenwald Fund, sprung up across the South. Today, of the 5,357 schools, shops, and teacher homes constructed, only 10 to 12 percent remain.[3]

(Map of Rosenwald schools built in fifteen states by 1932. Digital image courtesy of the National Park Service.

The map is available at Fisk University, John Hope and Aurelia E. Franklin Library Special Collection, Julius Rosenwald Fund Archives.)

The last remaining Rosenwald school in Williamson County is called Lee-Buckner. Lee-Buckner was one of 375 Rosenwald schools in Tennessee when the doors opened to its first students in 1927. The intentionality of its architecture, including its north-south orientation, placed windows on the east and west side of the school, bringing light over student’s shoulders, lessening eye strain. Ventilation, heating, and sanitation were also critical aspects of progressive school design. As such, Rosenwald schools resonated community identity and aspirations.[4] Charles Buford, a former student of Lee-Buckner recalled, “This building taught us all we could be somebody in life.”[5]

(Lee-Buckner Rosenwald school, c1927. An important feature of Rosenwald schools was directional orientation, allowing natural light and proper ventilation. Image courtesy of Fisk University, Fisk University Rosenwald Fund Card File Database.)

By 1940, Lee-Buckner was one of 24 African American schools in Williamson county. Headed by Miss Thelma E. Davis, the one-room schoolhouse in the rural Duplex community, educated 56 children, grades 1-8, that year. Though crowded, the school was a modern design when constructed with support from the Rosenwald Fund. Children attending in 1940, came from families like the Lees, Bufords, Christmons, Baughs, Grigsbys, and others who attended Lee-Buckner for decades. They were the children of farmers, sharecroppers, and laborers. The school began c1868 with support from the Methodist Episcopal Church, North as the Rural Hill Methodist Church. As slavery ended and freedom began, churches and schools were often one in the same – places that fed, blessed, and educated their communities.

(Lee-Buckner, c1942. The original school and church, Rural Hill, remains visible to the east. An addition to Lee-Buckner in the mid to late 1940s, provided supplementary space. It is believed Rural Hill was disassembled by 1950. Image courtesy of Tennessee State Library and Archives.)

The earliest known teacher was William P. Lloyd, an Ohio-born minister. Intimidation from local whites and the inability of the African American community to pay Mr. Lloyd likely forced the school to close for several years. By 1873, more than 200 African American children attended school in the 11th District including Rural Hill. In 1876, Williamson County school records show children from the families of Baugh, Steel, Waddy, Lee, among others attending.

(Image of the Rural Hill Methodist Church and School, c.1925. From A Study of Local School Units in Tennessee, Tennessee. Dept. of Education, 1937.)

Many of the earliest teachers, like Cynthia Waddy, received training at Tennessee Central College – an institution supported by the Methodist Episcopal Church, North. Waddy, a native of Rutherford County, attended Tennessee Central in the late 1890s and early 1900s. She taught at Lee-Buckner from 1915 until 1931. Historian Thelma Battle’s oral history with Dinah Lee Smith (1924-2012) is one of the earliest memories of Lee-Buckner and the African American Duplex community:

(Mrs. Cynthia Howse Wright Waddy, c1913. Image courtesy of The Nashville Globe, Newspapers.com)

(Mrs. Cynthia Howse Wright Waddy, c1913. Image courtesy of The Nashville Globe, Newspapers.com)

“We (Lee family) used to own all that property…it was just a solid farm…We lived way out in the country…I started school when I was five-years old…My schoolteacher was “Miz Cynthia Waddy.”…I went to Lee-Buckner School…I ‘wadn’t nowhere’ [didn’t live far] from the school. The school was on the topside of our property.I walked up to the fence…got over the fence and went into the school.[6]”

The Lees were part of the original founding of the Rural Hill Church. Anderson Lee, born a slave in Virginia, was a founder of the Rural Hill Church. His son, Monroe, also born in slavery and father of Dinah, sold the land to Williamson County for the construction of Lee-Buckner in 1925 for $125. Following Mrs. Waddy, Miss Thelma Davis arrived as the new teacher. Educated at Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial College (Tennessee State University), Miss Davis taught at the school from around 1933 until it closed in 1965. A second teacher joined the faculty in 1942 taking over the younger grades.

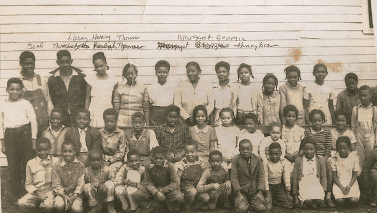

(c1948 of the students attending Lee-Buckner. Image courtesy of Mrs. Georgia Harris, personal photograph collection.)

(c1948 of the students attending Lee-Buckner. Image courtesy of Mrs. Georgia Harris, personal photograph collection.)

Roy Brown, in a 2019 oral history recalled his teacher, whom he called “Miss Davis,” even though she married:

“Yes, she was the upper-class teacher and she was also the principal. She had a dual function, which the principal’s position at that time wasn’t regarded as being a high position because mainly all she did was she signed all the report cards. Where it says “Principal,” her name was there. So she was a great teacher, and like I said a very likable lady. She had no kids, and she did drive back and forth from Franklin to Duplex.[7]”

As the last remaining Rosenwald school in Williamson County, Lee-Buckner is an enduring reminder that separate was not equal. A 1951 survey of Williamson County schools found 3 of the 22 “colored” elementary schools rated in “poor” condition, while the remainder rated “unsatisfactory.” Although in poor repair, Lee-Buckner was “structurally sound.” As rural schools closed in the South throughout the 1950s and 1960s, especially after desegregation, many transformed into community centers, churches, private homes (as did Lee-Buckner until the 2000s) or simply fell into disrepair.

Today, Rosenwald schools that survive symbolize the visionary promise of Booker T. Washington and Julius Rosenwald, the historic struggle of equal educational opportunities for African Americans, and a hope for an equitable future. Lee-Buckner is an important part of our collective past in Williamson County. Saving the school allows us to revive its story. But, to save it, we must relocate it. In the coming months, Lee-Buckner will hopefully move to Franklin Grove Estate & Gardens. Once secured on a permanent foundation, Lee-Buckner will undergo a full restoration and become an educational lab and museum featuring a permanent exhibit on its longstanding history alongside rotating exhibits on the African American experience nationally, regionally, and locally.

To learn how to become involved in the preservation efforts to restore this remarkable artifact, please visit our website https://williamsonheritage.org/leebuckner.

(Though boarded up, original windows remain. Interior image of the industrial room/kitchen at Lee-Buckner, August 2020.

(Though boarded up, original windows remain. Interior image of the industrial room/kitchen at Lee-Buckner, August 2020.

Image courtesy of the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County.)

(The iconic beadboard inside of Lee-Buckner, July 2020. Image courtesy of Grace Abernethy.)

(The 1940s addition to Lee-Buckner included a larger room and a front porch, August 2020.

Image courtesy of the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County.)

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Heritage Foundation of Williamson County, “TRAILER: Saving an Endangered Rosenwald School and Its Iconic Stories,” November 19, 2019, video, 2:41, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6mySC60H2PA. (accessed September 28, 2020).

[2] Mary S. Hoffschewelle, The Rosenwald Schools of the American South (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2006), 96.

[3] The National Trust for Historic Preservation, Rosenwald Schools. https://savingplaces.org/places/rosenwald-schools#.X3ObA2hKiUk. (accessed September 28, 2020).

[4] Hoffschwelle, 96. Also see, Mary S. Hoffschewelle, “Preserving Rosenwald Schools” (Washington, D.C.: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2012), 10-15. https://forum.savingplaces.org/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=693200ab-b3c9-7ee9-f177-6ed15bcd491b. (accessed September 29, 2020).

[5] Heritage Foundation of Williamson County, “TRAILER: Saving an Endangered Rosenwald School and Its Iconic Stories.”

[6]Thelma Battle, Raining in the House and Leaking Outdoors: A Cultural and Photographic Presentation: 100 Local African American Women over the Age of 65. (Franklin: Z’Atelier Publications, 2006),

[7] Brown, Roy. 2019. Interview by Sheree Scarborough. March 19. Completed interview transcript, Heritage Foundation of Williamson County Oral History Project, Franklin, TN.