Herstory Is Our History: Women Changemakers in Community Activism

Compiled by the Heritage Foundation’s Preservation and Education team

Women suffragists marching on Pennsylvania Avenue led by Mrs. Richard Coke Burleson (center on horseback); U.S. Capitol in background, c1913. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.[1]

Women’s history is America’s history. It’s a storied struggle of civil rights, human rights, equality, and equitable consciousness, that even today is woven into the fabric of our collective conversations. Since the inception of our nation, women created, participated in and remain deeply connected to socioeconomic and political change. Now more than ever, historic organizations, historic sites and museums are using a critical lens to examine the lives of women – all women – who played and continue to play, a vital role in shaping voting rights and equality for all.

When the United States Constitution became the framework of our government, it was silent on the rights of women. And yet, women actively participated as citizens for change – marching, petitioning, organizing, boycotting, mobilizing – since the beginning of our country. Women’s tireless work redefined the opening statement of the Preamble to the Constitution, “We, the People,” changing generational perceptions and passivity into action.

In the upcoming weeks, the Heritage Foundation will launch its first interpretive traveling exhibit focused on the Women’s Suffrage Movement. Through research, we recognize Williamson County’s rich women’s history tied to America’s story. Inspired by female leaders, locally and nationally, please enjoy a few inspirational “Herstories” who led the way for women’s suffrage and equality.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton – Waterloo, New York (1815-1902)

Elizabeth Cady Stanton with her sons Daniel and Henry in 1848, the year of the Seneca Falls Convention (Photo credit Wikimedia.)[2]

At the age of 32, Elizabeth Cady Stanton was the originator of the Declaration of Sentiments at the first Women’s Suffrage Convention at Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848, declaring, “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness…”[3] Stanton, a key figure in the women’s suffrage movement, pushed not only for voting rights, but women’s rights for birth control, property, employment, education, and parental rights. A meeting with Susan B. Anthony in 1851 propelled them to national leadership roles in the movement.

Susan B. Anthony – Adams, Massachusetts (1820-1906)

Susan B. Anthony is one of the most recognizable figures of the national women’s suffrage movement. An author, activist, abolitionist, educator and speaker, Anthony catapulted to national notoriety as President of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. In 1849, while campaigning against the use of alcohol, she was denied the right to speak simply because of her gender.

It was in that moment Anthony realized until women had the right to vote they would not have a voice. In 1851, Anthony met Elizabeth Cady Stanton at an anti-slavery conference. Together, they campaigned for women’s rights through the formation of the New York State Women’s Temperance Society and New York State Women’s Rights Committee. Following the Civil War, Anthony traveled the country speaking on the importance of women’s rights and voting rights.

She and Stanton established the American Equal Rights Association in 1866, demanding the same rights be granted to all regardless of race or gender. They produced a weekly newspaper, The Revolution, whose motto “Men their rights, and nothing more; women’s rights, and nothing less,” culminated with their formation of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1869. [4]

Anthony was arrested for illegally voting in the presidential election of 1872, and in 1905, she lobbied President Theodore Roosevelt for an amendment to give women the to vote.

A public relations photograph taken between c1855-1865 and published in the History of Woman Suffrage, Volume 1, by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony in 1881.[5]

Anne Dallas Dudley – Nashville, Tennessee (1876-1955)

Tennessee women’s suffrage leader Anne Dallas Dudley is pictured here with her two children, Trevania and Guildford Dudley Jr. This image was strategically used by Anne Dallas Dudley in women’s suffrage publicity materials to counter negative stereotypes that suffragists were mannish, childless radicals intent on destroying the American family. Image courtesy of the Tennessee State Library and Archives.[6]

Anne Dallas Dudley was a national and state leader for the women’s suffrage movement. Dudley founded the Nashville Equal Suffrage League to diligently build local support and served as its president beginning in 1915. She organized large “May Day” suffrage parades led by she and her children. Nashville was the first suffrage parade in the South. Dudley industriously campaigned for the final ratification of the right to vote in August of 1920. She once shut down an anti-suffragist’s argument that “because only men bear arms, only men should vote,” to which Dudley strategically replied, “Yes, but women bear armies.”[7]

Dudley strategically brought the National American Woman Suffrage Association conference to Nashville in 1914. Prior to the conference, Dudley traveled throughout Tennessee mobilizing and organizing local leagues in cities like Franklin. She not only introduced suffrage legislation to the Tennessee constitution but also gained suffrage support from both political parties.

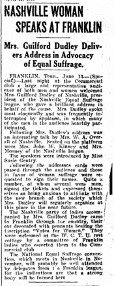

Anne Dallas Dudley traveled to Franklin to speak to the newly formed Equal Suffrage League in Franklin, Tennessee in June 1914. Image courtesy of The Tennessean from Newspapers.com[8]

Ida B. Wells-Barnett – Holly Springs, Mississippi (1862-1931)

Ida B. Wells was an African American journalist, abolitionist, and feminist who led one of the largest anti-lynching crusades in the United States in the 1890s. She was a co-founder of the National Association of Colored Women in 1896. Image courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.[9]

Ida B. Wells, an African American journalist, abolitionist, and feminist, experienced sexism, racism, and violence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born during the Civil War, Ida became an activist for equal rights after she was thrown off a first-class train, despite holding a first-class ticket in 1884. She sued and won in the local Memphis court, but the ruling was overturned in federal court. After her friend was lynched, she keenly focused her efforts, publishing an exposé on the subject. Her writings enraged locals in Memphis (1892.)

With her life threatened, she moved to Chicago and married African American attorney Ferdinand Barnett. Ida traveled globally, enlightening foreign audiences to the realities of lynching in the U.S. She openly confronted white women in the suffrage movement who repeatedly ignored the horrors of lynching, who in turn, ridiculed her. Ida remained undeterred, co-founding the National Association of Colored Women, created to address civil rights and women’s suffrage. In her later years, she pushed for urban reform in African American neighborhoods of Chicago.[10]

Sue Winstead, Franklin, Tennessee (1889-1981)

A niece of William E. Winstead and cousin to Katie Neil Winstead White, Sue Winstead was one of the first women in Franklin to organize and mobilize Franklin’s local chapter of the Equal Suffrage League. She held several meetings in her home. Relational ties between the families of Franklin and Nashville assisted the formation of a local Franklin chapter. Prominent women of Franklin involved in the Equal Suffrage League of Franklin included Miss Emily Colley, Mrs. Dosey Crockett, Ms. Suzie Gentry, Mrs. Pryor Lillie and Mrs. Edwin Maury (Caro) Perkins. Sue Winstead later moved to Los Angeles, California, with two of her cousins and worked as a librarian, remaining a steadfast voter and active in women’s rights until her death.

Bridal party hosted by Katie Neil Winstead White for her cousin, Bettie Briggs Winstead, at Winstead Place, Franklin, Tennessee, in 1907. Seated is Bettie Briggs Winstead. From left to right, Tillie Briggs, Sue Winstead, Agnes Bennett, Mattie Briggs Henderson, Katie Neil Winstead White, Tot Woods, Agnes Gordon, Virginia Fitts Warfield, Anne Kenneday, Tillie Sowell, and Bessie Lee Duvall. Today, Winstead Place is owned by the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County is has been renamed Franklin Grove Estate & Gardens. Image courtesy of the Williamson County Historical Society.[11]

For local African American women, community formed the basis of their suffrage organizations. In 1910, the Forget Me Not Club formed in Franklin and today, remains the oldest active African American women’s organization in the local community. The descendants of formerly enslaved men and women – including the Oteys, Winsteads, Scruggs and Perkins — met to teach and inspire each other domestically. However, while focused on recipes and sewing, they also galvanized support for changes in education, employment, and women’s suffrage.

The Forget Me Not Club was the first African American female-led organization for the purpose of mobilizing women to engage and empower each other in and outside of their homes in Franklin, Tennessee, in 1910. Many female leaders of the Forget Me Not Club were descendants of formerly enslaved men and women of Franklin and Williamson County. Image courtesy of the Williamson County Historical Society.[12]

As the Heritage Foundation promotes dynamic preservation and education programming, we aspire to elevate local places of women’s history by advocating for preserving places and reshaping the narrative to include all women. We hope to inspire the next generation of women who see their future in preservation and challenge ourselves to be a part of spearheading that effort. But this is only the beginning. Like the Women’s Suffrage Movement, it begins with a spark. Through the preservation of sites and stories, let us all work together to tell the whole story, “Herstory,” of our county and our country.

ENDNOTES:

[1] Women’s Suffrage Parade, Washington, D.C. c1913. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/97500042/ (Accessed October 29, 2020.)

[2] Elizabeth Cady Stanton and her two sons, c1848. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/2006683458/ (Accessed October 30, 2020.)

[3] Declaration of Sentiments, Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention, Seneca Falls, NY,1848. https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/declaration-of-sentiments.htm (Accessed October 30, 2020.)

[4] Susan B. Anthony’s Biography, Biography.com https://www.biography.com/activist/susan-b-anthony (Accessed November 2, 2020.)

[5] Susan B. Anthony, Image from Wikipedia.org. (Accessed October 30, 2020.) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Susan_B_Anthony_c1855.png

[6] Anne Dallas Dudley with her two children, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Tennessee Virtual Archive, https://teva.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15138coll27/id/69/ (Accessed November 2, 2020.)

[7] Biography of Anne Dallas Dudley, The Tennessee Suffrage Monument Association, Nashville, Tennessee.

https://tnsuffragemonument.org/ (Accessed November 2, 2020.)

[8] “Nashville Woman Speaks At Franklin” The Tennessean, June 14, 1914. Newspapers.com (Accessed October 30, 2020.)

[9]Biography and image of Ida B. Wells, original image held at the Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. https://www.biography.com/activist/ida-b-wells (Accessed October 30, 2020.)

[10] Biography of Ida B. Wells, National Museum of Women’s History, Alexandria, Virginia. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/ida-b-wells-barnett (Accessed October 30, 2020.)

[11] Bridal party hosted by Katie Neil Winstead White for her cousin, Bettie Briggs Winstead, at Winstead Place, Franklin, Tennessee, in 1907. The historic Winstead House is owned by the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County is has been renamed Franklin Grove Estate & Gardens. Image courtesy of the Williamson County Historical Society. https://www.flickr.com/photos/heritagefoundationfranklin/4746648826/in/photolist-KhKmsa-owsMDj-odLDfx-hFA51E-8B4bD7-hFB2n1-8erPjS-bjbsXR-2jHHHPJ-2jJ1Rze-5JYT4K. (Accessed October 30, 2020.)

[12] The Forget Me Not Club, Franklin, Tennessee, 1910. Image courtesy of the Williamson County Historical Society. https://www.flickr.com/photos/heritagefoundationfranklin/ (Accessed October 29, 2020.)