McLemore House: A Story of Trials and Triumph

Situated in the heart of Hard Bargain on the west side of downtown Franklin sits one of Franklin’s most remarkable historic properties, McLemore House. Currently owned by the African American Heritage Society of Williamson County, its roots are deeply intertwined with both hardship and triumph. Originally owned by former enslaved person Harvey McLemore, it stands today as a living testament to the determination and resilience of Williamson County’s freed citizens following the Civil War and into the 20th century.

From Slavery to Property Ownership

The McLemore story begins under the chains of slavery; Harvey McLemore (ca. 1829 – ca. 1898) first appears in historical records in a bill of sale, purchased by Atkins and Bethenia McLemore, owners of a 427-acre plantation south of Franklin. While much is not known about the details of his life during his youth and enslavement, he is repeatedly mentioned in estate inventory and court records until 1850. Additionally, Mrs. McLemore sold Harvey to her son, William Sugars (W.S.) McLemore in 1859 for $1,100 – not only a considerable amount for that time but also an unusual transaction given that estate property was usually willed to descendants rather than sold.

W.S. McLemore served as a Confederate Civil War calvary officer, lawyer, and judge and amassed several tracks of land throughout the county as well as seven slaves other than Harvey. Following the Emancipation Proclamation in 1865, Harvey signed his first work contract as a free man with his former owner to cultivate nearly 40 acres of land and cotton. Despite the opportunity to work freely, these contracts still put newly freed persons at a severe disadvantage, requiring them to “supply everything needed to cultivate said land” as well as relinquish over one-third of profits in exchange for use of the land.

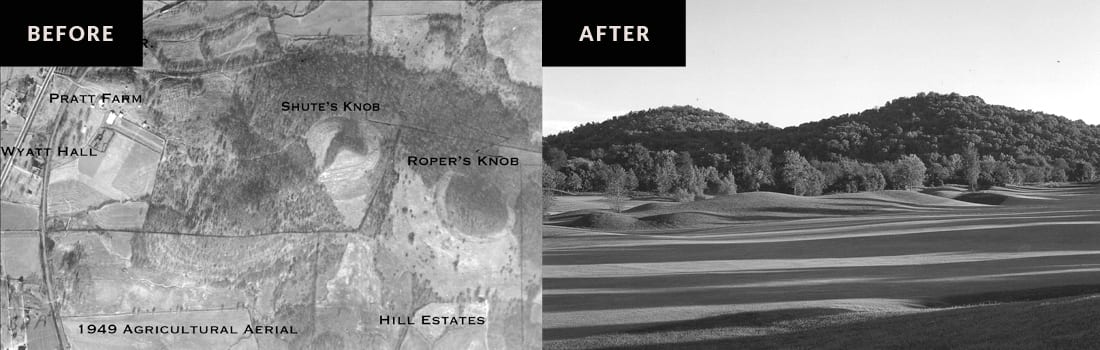

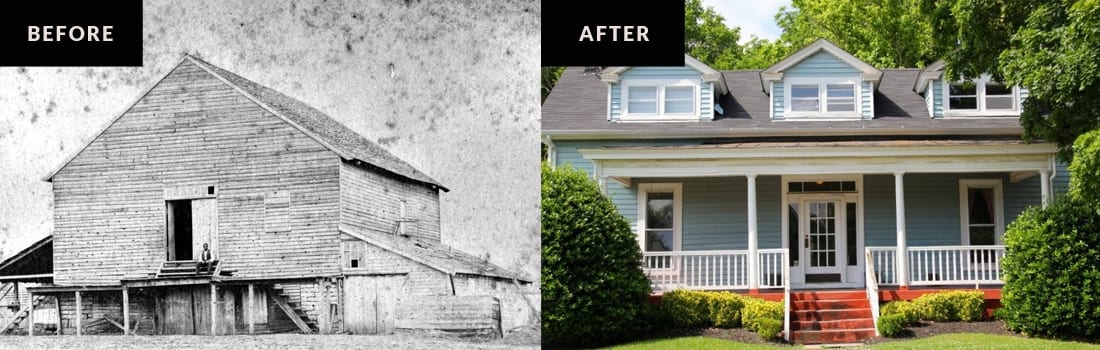

By 1870, Harvey had married his wife, Eliza, and managed 68 acres of land on the McGavock Plantation, now known as Carnton. In 1880, he purchased four lots from W.S. McLemore for $400, the largest amount of property owned by any African American in Hard Bargain. He then built his home, which served as protection and a source of income for his family for the next 117 years.

The Reconstruction years offered a period of hope and renewal for Franklin’s African American community. Several neighborhoods flourished along Natchez Street, along a section of Columbia Avenue, a small area along Second Avenue south, and at Hard Bargain. Despite few opportunities for a formal education, Harvey and many of his community members prevailed and thrived due to their work ethic and commitment to providing hope and a future for their families. Hard Bargain grew into a strong community of skilled African American laborers, who were specialized carpenters, rock masons, blacksmiths, mill workers, washerwomen, and domestic servants.

Upon his death in 1898, Harvey left his home to his wife, Eliza, with specific instructions to pass it on to his only daughter, Mary Matthews, who worked as laundress and domestic servant. However, Mary’s ownership was challenged in court for many years, though she fought successfully to retain what was rightfully hers. In 1883, Mary married Henry Matthews, and they lived with Harvey until his death, after which ushered in a new chapter of domestic abuse in their marriage. The Chancery Court granted Mary a divorce in 1901, giving her custody of their five children and affirming her right to the home. She later remarried Robert Hunter in 1918.

A Legacy of Stewardship

Mary Matthews was the first of many strong African American women who stewarded the property well over the next century. Her daughter, Maggie, seized educational opportunities and commuted to Nashville’s first African American Catholic school, Immaculate Mother Academy, for high school. After World War I, she joined the growing number of women seeking self-employment as a professional hairdresser, studying cosmetology in Nashville and New York City, even attending Antoine’s in New York around 1938. Upon the completion of her studies, she returned to Hard Bargain and opened her own beauty salon in the front hallway of her home – the home her formerly enslaved grandfather constructed himself as a promise for their future.

Maggie’s salon business nurtured the local female African American community, offering a hub to gather, share, and support one another. Enjoying a long and successful career as a business owner, Maggie lived in the home until her death in 1989.

The Impact of $1

Laverne Holland, Harvey’s great, great granddaughter, was the last descendent to occupy the home. In 1997, The Heritage Foundation of Williamson County, led by Executive Director Mary Pearce, partnered with Habitat for Humanity to purchase the property from Maggie Matthews’ estate. That same year, the African American Heritage Society of Williamson County was founded to continue telling the important stories of African Americans in the community. The Heritage Foundation, in a gesture of goodwill, subsequently sold the McLemore House to the newly formed society for $1, and they opened it as the African American House Museum in 2002.

Today, the McLemore House serves as a powerful reminder of the trials and triumphs Williamson County African Americans endured on the path to equality and freedom. From its early days as a haven of protection for the Harvey McLemore family to the birth of women’s entrepreneurship, the stories inherent in its walls encourage all who visit to honor the sacrifices and hardship that bore its success.