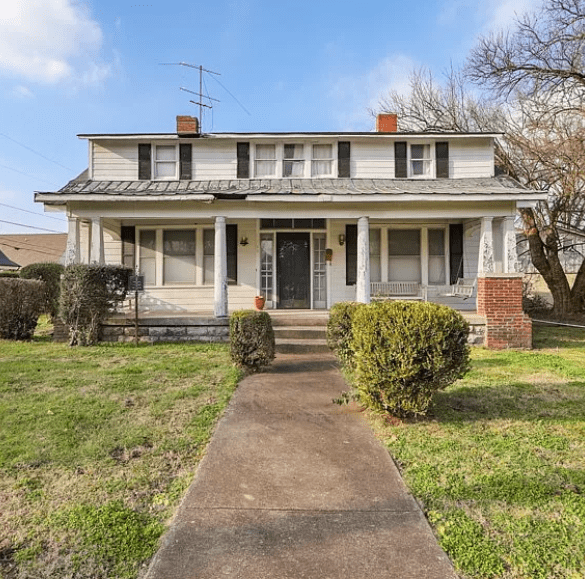

The Merrill-Williams house sits in the Natchez Historic District, recognized by the U.S. Department of the Interior through the National Park Service. The Natchez Street neighborhood was nicknamed “Baptist Neck” by local residents in the early 1900s because of the three churches located along Natchez Street: Shorter Chapel A.M.E., First Missionary Baptist and Providence United Primitive Baptist.

Three generations of the family lived in this home. In 1881, Tom Williams built the white six-room home that now sits on the property. In 1950, Fred D. Williams, the grandson of A.N.C. Williams, and his wife, Mattie, purchased the house in which current owner Cassandra Taylor grew up.

The Williams family transformed the house into a cultural hub for the Natchez community during the era of segregation, when they hosted art shows and musical performances. AAHS President Alma McLemore said, “The Williams family turned the property into a Natchez Street showplace…. Merchants, musicians, educators and antique collectors, the Williams family and their house became a neighborhood institution for the next 100 years.”

The house sat vacant after the death of Taylor’s mother in 2009. It was listed for sale in November 2020, and many feared the home would be threatened with gentrification or demolition if sold, given the lack of inventory in the Williamson County real estate market. But in April 2021, leaders of the African American Heritage Society of Williamson County and other community partners announced a campaign to acquire and save 264 Natchez Street.

The AAHS now has a legal option to purchase and renovate the house into a cultural center. They say the project will require $1 million dollars: $610,000 to purchase the house, with the remaining for restoration and opening of the center. Funds raised to date covered the escrow, but they are still accepting donations at https://gofund.me/0f047dc6.