WHY THIS BUILDING MATTERS

by Rachael Finch, Senior Director of Preservation & Education

Join us as we uplift the Lee-Buckner Rosenwald School, its history within the Duplex Community of Southern Williamson County, and our preservation plan to relocate and restore the school at Franklin Grove Estate & Gardens.

Following the Civil War, newly freed African Americans quickly established schools, cemeteries, and churches. Of the three, churches were the cornerstone – the nucleus – that symbolized community. Churches became anchor institutions of African American communities because many also served as schools. As vital as education and religion were to African Americans so to were places of memorialization. Cemeteries were vital gathering places to properly remember and bring dignity to the dead. Enslaved, commoditized, and deprioritized by their former slaveowners, who did not provide nor prioritize their enslaved even in death, African Americans saw cemeteries as crucial tools for individuals to commemorate and remember their loved ones in a humane way. The Lee-Buckner Rosenwald School holds a remarkable history, and we are grateful for the opportunity to save it, relocate it, restore it, and share its stories with the public. But to understand the Lee-Buckner Rosenwald School and its significance, we must first tell the story of Rural Hill.

Rural Hill

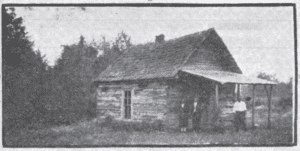

In 1867 one half acre of land was formally purchased from Guilford Dudley by African Americans Anderson Lee, Samuel Crow, and William Stevenson to be used “for the colored people of this vicinity to be used for church and school purposes.”[1] By 1868, the Rural Hill Church and School construction was under way. The first teacher, William P. Lloyd, reported on the construction noting that the “schoolhouse has no floor or windows” but was “a good house so far as the colored people have been able to complete it.”[2] The completed building with log construction, included one door, one window, and a front porch.

Rural Hill M.E. Church and School. Photo from A Study of Local School Units in Tennessee.

The Rural Hill African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church served a dual purpose for the Black community, a church and a school. The only photographs of the structure, taken around 1925, show a small log-built school poorly lit and poorly ventilated with perhaps a window on each side. Prior to the construction of the Rosenwald School in 1927, the Rural Hill School served grades 1-8. The primitive structure sat as many as 30 students on long benches taught by one teacher perhaps equipped with a blackboard and used textbooks.[3]

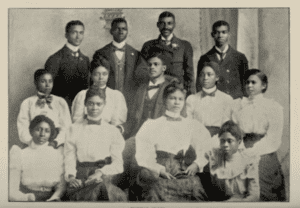

Even though the documentation for Rural Hill A.M.E. Church and School is scarce, there is enough information to show a relationship between the Methodist Episcopal Church and Rural Hill. The deed for the Rural Hill Church, recorded in 1872 shows Rural Hill’s affiliation with the Methodist Episcopal Church, North. By May 1918, “a grand concert…at the M. E. Church” signaled the end of the school term at Lee-Buckner.[4] It was at this time, the name Lee-Buckner was formally used to describe the school contained within the walls of Rural Hill Church. Extant catalogs from Central Tennessee College, once located in Nashville, contain the names are several Duplex-area students: Lundy Steele, Lena Williamson, Janie Alice Lee, Willie Allen Lee, Thomas Waddy, and Martin Waddy.[5] Janie Alice Lee would go on to teach at Lee-Buckner and Martin Waddy would marry one of her successors.

The Census in 1900 lists many Duplex-area children as “at school,” but, unlike 1880, the enumerator did record a teacher. Perhaps Harriett Baugh, Laura McKissick or another literate black woman or man in Duplex took on the task of teaching the children. In 1908, the first-year records are available, “Janie Overton” was paid $22.50 for teaching her 7th month at “Lee school” in the 11th District.[6] Janie Alice Lee, the daughter of Monroe Lee and granddaughter of Anderson Lee, attended Central Tennessee College from 1895 to 1898.[7] She married John Overton in 1899.[8] Overton was likely a relative of Docke Overton, who married Rural Hill teacher Eliza Baugh a decade earlier.

Normal Class at Central Tennessee College, 1898. (Central Tennessee College catalog, Archive.org.)

In 1910, Miss Johnnie Leek, a twenty-one-year-old public-school teacher, boarded with the Monroe Lee family. Leek graduated in 1908 from the school at Brooks Chapel M.E. in Brentwood. She may have been the first teacher at Rural Hill, since Reconstruction, not directly connected to Duplex.[9] A year later, Leek was teaching back home in Brentwood.[10] In 1912, county records show Missouri Overton, daughter of Eliza Baugh and Docke Overton, teaching at Rural Hill. She received $14 for “teaching last 3 wks at Lee (Rural Hill).”[11] Two more teachers—Mrs. Jimmie Moore [Alberta Hobbs Moore] and Lena Boyd—would follow, but Mrs. Cynthia Mae Wright (nee Howse) would be one of the longest-serving teachers at Lee-Buckner. Howse, born in Rutherford County, attended Central Tennessee College in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Around 1905, she moved to Sherron in Weakley County, Tennessee to teach. At the M.E. Church in Sherron, she married a fellow teacher, Charles Wright and the couple soon returned to the Nashville area.[12] Charles died in March 1914 and by February 1916, Mrs. Wright was teaching at Lee-Buckner.[13] There she met Martin E. Waddy; the couple married on February 6, 1916.[14] Cynthia Waddy taught at Lee-Buckner until the end of the 1931-1932 school year.[15]

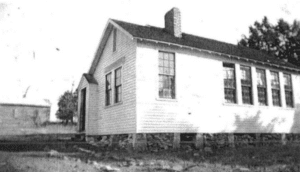

Miss Thelma Elizabeth Davis began teaching at Lee-Buckner in 1933. She had already taught two years at Florenceville and one at Cedar Hill.[16] Davis, a native of Franklin, lived in Franklin and drove to school every day. Davis was part of a generation of teachers who attended Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial College (today, it is Tennessee State University), the public college for African Americans that opened in Nashville in 1912.[17] In 1935, Davis had a full classroom of 49 students—26 boys and 23 girls. Grades 1-8 were taught at Lee-Buckner, but no 7th or 8th graders attended that year. The children—Lees, Baughs, Adkissons, Browns, Christmas, Odens, Steeles, and others—all lived between a ½ mile and 3 miles from the school. Their parents were farmers and laundresses.[18] In 1942, a second teacher, Mrs. T. A. Williams was added to Lee-Buckner’s faculty. The next year, Geneva A. Fuller, a Tennessee A&I graduate, replaced Williams.[19] Initially, the second teacher taught the lower grades (1-4) in the old Rural Hill Church, still standing. Georgia Baugh Harris, who attended elementary school in the mid-1940s, recalled the old church and a pulpit still in the building.[20] A second classroom was added to the east side of the 1927 Rosenwald school by 1955.[21] The two rooms were divided by a partition with access between the two rooms via pocket doors.[22]

Students pose outside Lee-Buckner around 1948 on the east side of the building, before the addition of the second classroom. This image is from a booklet published by Williamson County School Board. Many of the images have been scanned by Williamson County Historian Rick Warwick, but a copy of the booklet has been elusive. (Courtesy of Williamson County Historian Rick Warwick.)

A 1951 survey of Williamson County schools found all twenty-two “colored” elementary schools were rated in “poor” condition. Although in poor repair, Lee-Buckner was considered “structurally sound.”[23] The survey recommended school consolidation in rural areas. For black schools in southern Williamson County, the authors believed “A center for Negro elementary school pupils as Thompson’s Station would be within easy transportation distance of Pearly Hill, Mount Lavergne, Lee-Buckner, Cedar Hill, Goose Creek, and Fitzgerald.”[24] However, the authors also made recommendations for retaining Lee-Buckner:

It might be desirable to retain the Lee-Buckner School until a later stage in the long-range program. If this building is continued in use, the interior should be painted, and it should be rewired for adequate lighting. Other improvements should be made such as jacketing the stoves; re-slating chalkboards; installing window shades, new seats, and equipment. Increased attention must be given to maintenance. For example, there is no knob or lock on the front door.”[25]

Williamson County consolidated small rural schools by the early 1950s. By 1954, the county had 10 black elementary schools—down from 23 in 1951. In 1961, the county had seven Black elementary schools.[26] As the county consolidated rural schools, Tennessee’s Jim Crow laws and segregated public schools were upended by the Civil Right movement and the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas which found segregated schools unconstitutional.[27] Still it would be a decade before Williamson County began to desegregate its schools.

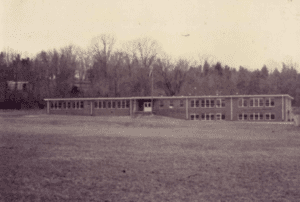

Evergreen was then constructed near Thompson’s Station in 1965 to consolidate three black schools—Thompson Station, Lee-Buckner, and Westwood—and avoid integration. Still facing federal pressure, the school board abandoned this plan and merged the three black schools with white students from Thompson Station and Burwood.[28] With the consolidation, Lee-Buckner closed after the 1964-1965 school year. That year Mary Alice Steele, a Tennessee A&I graduate, taught 28 students in the lower elementary, Thelma (Davis) Radcliffe taught 27 upper-level students.[29]

Evergreen was built in 1965 to consolidate three Black elementary schools, including Lee-Buckner, into one and avoid integration. (Courtesy of Williamson County Historian Rick Warwick.)

With the county no longer using Lee-Buckner, it was sold. With little fanfare for the once proud symbol of Duplex’s Black community and its nearly 100 years of achievements and educational history it was sold. A hand-written and undated note in the Williamson County Archives says, “Lee-Buckner School sold to James N. Burch, Spring Hill, Tenn. Buckner Road” for $1125.00.[30] Hattie Baines, in a 2019 oral history, recalled her sister-in-law, “Sis,” and brother, Frank McCullough, bought the school from Williamson County around 1965, using it as a home. Baines purchased the property after “Sis” died in the late 1990s or early 2000s and her brother moved out.[31] The property has been vacant since then.

New Horizons for Lee-Buckner Rosenwald School

While there is not a complete written record depicting the entire picture of the Rural Hill/Duplex community, particularly of its Black citizens, its history and culture are worthy of significant study and recognition within the cultural landscape of southeastern Williamson County. The Duplex community that existed and evolved over decades, was predominantly Black, and yet, little is known of its vibrancy. Often the best understanding of a community – its landscape – is derived from a study of its physical, geographical, and cultural characteristics as well as research of all records – deeds, maps, tax, and probate records. To truly understand the significance of the Lee-Buckner Rosenwald school, primary and secondary sources, including church records, oral histories, historic newspapers, deeds, probates, educational and census records continue to afford us the opportunity to engage not only with the Lee-Buckner Rosenwald School as a building, but as a pillar of the Duplex community’s complex, yet vibrant, cultural landscape.

Philanthropist and President of Sears, Roebuck & Co. Julius Rosenwald with the founder of Tuskegee Institute Booker T. Washington, at Tuskegee Institute, February 22, 1915. (Image courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.)

As the last remaining Rosenwald School in Williamson County, Lee-Buckner Rosenwald School, its history, and its architecture are not just another “site of memory,” but a lasting and important reminder of early twentieth century African American life; a clear representation of separate but not equal. Built in 1927, the Lee-Buckner Rosenwald School is the only surviving Rosenwald standing in Williamson County, Tennessee, and became the first rural Rosenwald School constructed in the county. Its construction was funded by a combination of sources from the Williamson County Board of Education, white and black citizens, and the Julius Rosenwald Fund that bridged the educational divide in the rural South for Black children to receive equal nobility, in the classroom and from the classroom.

Prior to the creation of Rosenwald schools, many Black children sought education inside of churches and barns, without proper supplies, and at times, without teachers. In collaborative spirit, Booker T. Washington, founder and president of Tuskegee Institute and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears, Roebuck, & Co, formed a unique partnership and engaged in a radical experiment to bridge the educational divide by building these schools to help support educational equality for Black children in the southern United States. Rosenwald schools modeled progressive theory and practice, provided sanctuary, and secured instructional opportunities. Between 1912-1932, thousands of schools, financed in cooperation by communities and the Rosenwald Fund, sprung up across the South. Today, of the 5,357 schools, shops, and teacher homes constructed, only 10 to 12 percent remain.[32]

Lee-Buckner was one of 375 Rosenwald schools in Tennessee, when the doors opened to its first students in 1927. The intentionality of its architecture, including its north-south orientation, placed windows on the east and west side of the school, bringing light over student’s shoulders, lessening eye strain. Ventilation, heating, and sanitation were also critical aspects of progressive school design. As such, Rosenwald schools resonated community identity and aspirations.[33] Charles Buford, a former student of Lee-Buckner recalled, “This building taught us all we could be somebody in life.”[34]

Lee-Buckner, c1942. The original school and church, Rural Hill, remains visible to the east. An addition to Lee Buckner in the mid to late 1940s, provided supplementary space. It is believed Rural Hill was disassembled by 1950. (Image courtesy of the Tennessee State Library and Archives.)

Today, Rosenwald schools that survive symbolize the visionary promise of Booker T. Washington and Julius Rosenwald, the historic struggle of equal educational opportunities for African Americans, and a hope for an equitable future. Lee-Buckner is an important part of our collective past in Williamson County. Saving the school allows us to revive its story. But, to save it, understanding its history is crucial to how it is restored, interpreted, and yes, even relocated to Franklin Grove Estate & Gardens. Preserving Lee-Buckner is not about just preserving a building; it is about preserving a community’s heritage and its history.

As the Heritage Foundation plans for the relocation and restoration of Lee-Buckner Rosenwald School, we will share more of its fascinating history through blogs and social media posts over the next few months. Please visit our website at www.williamsonheritage.org/lee-buckner-rosenwald-school/ or about our projects at https://williamsonheritage.org/historic-preservation/our-projects/.

______________________________________________________________________________

[1] Williamson County, TN, Deed Book 4:53.

[2] “Teacher’s Monthly School Report for the Month of April 1868,” Freedman’s Bureau.

[3] Tennessee State Department of Education, A Study of Local School Units in Tennessee (Nashville: Cullom & Ghertner & Co,, 1937), 12 accessed at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b58708&view=1up&seq=36; A similar image is included in the Fisk University Rosenwald Database, http://rosenwald.fisk.edu/?module=search.details&set_v=aWQ9NDE1MQ==&school_historic_name=lee%20buckner&button=Search&o=0; Carter Julian Savage, “Our School In Our Community: The Collective Economic Struggle for African American Education in Franklin, Tennessee, 1890-1967,” in Cultural Capital and Black Education, ed. V. P. Franklin and Carter Julian Savage (Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, 2004), pp. 49-79.; “The One-Room Schoolhouse,” The Tennessean, February 20, 1929.

[4] The Nashville Globe, May 24, 1918.

[5] Catalogue of Central Tennessee College, 1889-1900 accessed at https://archive.org/details/catalogue18891900cent/. Lundy Steele (1874) is identified as from Williamson County.

[5] The Nashville Globe, May 24, 1918.

6 Catalogue of Central Tennessee College, 1889-1900 accessed at https://archive.org/details/catalogue18891900cent/. Lundy Steele (1874) is identified as from Williamson County. Two other students from the community are Julia and William Major (1874, 1876) from Mt. Carmel. It’s not clear how the Majors were connected to Mt. Carmel (later called Duplex). The pair appears to have been married and were living in Christian County, Kentucky in 1880 according to the Manuscript Census. U.S., School Catalogs, 1765-1935, accessed on ancestry.com.

7 “Janie Overton” in “Lee-Buckner,” Williamson County School Invoices (unprocessed), Williamson County Archives; Janie Overton, buried in Duplex’s Spratt Cemetery, died in Chicago, Illinois in 1963. Her obituary reported she was the sister of Monroe Lee [Jr.] of Nashville, The Tennessean, January 23, 1963; Jane Lee is 2 years old in the 1880 Manuscript Census, Maury County, Tennessee. In 1900, Janie Overton, her husband, and 6-month-old son were living in Nashville.

8 Catalogue of Central Tennessee College, 1889-1900.

9 Janie A. Lee to John W. Overton, January 2, 1899, Tennessee, Marriage Records, 1720-2002, accessed on ancestry.com.

10 Nashville Globe, April 24, 1908. Brooks Chapel is identified as an “M. E.” in several newspaper articles, for examples, see Nashville Globe, October 29, 1909, September 21, 1917

11 Nashville Globe, August 25, 1911.

12 “Missouri Overton” in “Lee-Buckner,” Williamson County School Invoices (unprocessed), Williamson County Archives.

13 “Wright-Howse,” Nashville Globe, January 10, March 6, 1908.

14 “Charles Wright,” Tennessee, Death Records, 1908-1965, accessed on ancestry.com; “C. M. Wright” in “Lee-Buckner,” Williamson County School Invoices (unprocessed), Williamson County Archives; [stamped Feb 12, 1916]

15 Marriage License documents, M. E. Waddy and C. M. Wright, Tennessee, Marriage Records, 1780-2002, accessed on ancestry.com.

16 Registered teachers and minutes 1926-1931, Williamson County Archives. Also see Hoffschwelle,

[16] “Thelma Elizabeth Davis,” Personnel Record of Elementary Teacher or Principal, Williamson County School Invoices (unprocessed), Williamson County Archives.

[17] Thelma Elizabeth Radcliffe Funeral Program, Thelma Battle Collection, Special Collections, Williamson County Library; Roy Brown, Interview by Sheree Scarborough. March 19, 2019. Completed interview transcript, Heritage Foundation of Williamson County Oral History Project, Franklin, TN.

[18] 1935 Lee-Buckner, Williamson County School Census, Williamson County Archives.

[19] 1942 Lee-Buckner; 1943 Williamson County School School Census, Williamson County Archives.

[20] Georgia Harris, phone interview, August 24, 2020.

[21] A ca 1948 photograph of Lee-Buckner students, posed on the unaltered east side, shows the new addition was not complete. Georgia Baugh Harris says when she returned to the school in 1952, after an absence of several years, the addition was there. Georgia Harris, phone interview, August 24, 2020.

[22] Charles Buford, phone interview, August 24, 2020.

[23] George Peabody College for Teachers, Public Schools of Williamson County Tennessee: A Survey Report (George Peabody College for Teachers: Nashville, Tennessee, 1951), pg. 99, 103.

[24] George Peabody, Public Schools of Williamson County Tennessee, 132.

[25] Ibid, 132

[26] Warwick, editor, Black & White, 175-177.

[27] Cynthia G. Fleming, “‘We Shall Overcome’: Tennessee and the Civil Rights Movement,” in Tennessee History: The Land, the People and the Culture, ed. Carroll Van West (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1998), 442-446.

[28] Ibid, 178.

[29] 1964 Williamson County School Census, Williamson County Archives.

[30] Lee-Buckner Deeds in Williamson County School Invoices (unprocessed), Williamson County Archives.

[31] Hattie Baines, Interview by Sheree Scarborough. March 19, 2019. Completed interview transcript, Heritage Foundation of Williamson County Oral History Project, Franklin, TN.

17 Hoffschwelle, 96. Also see, Mary S. Hoffschewelle, “Preserving Rosenwald Schools” (Washington, D.C.: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2012), 10-15. https://forum.savingplaces.org/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=693200ab-b3c9-7ee9-f177-6ed15bcd491b. (Accessed January 26, 2023).

18 Hoffschwelle, 96. Hoffschewelle, “Preserving Rosenwald Schools” (Washington, D.C.: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2012), 10-15. https://forum.savingplaces.org/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=693200ab-b3c9-7ee9-f177-6ed15bcd491b. (Accessed September 29, 2020).

19 Heritage Foundation of Williamson County, “TRAILER: Saving an Endangered Rosenwald School and Its Iconic Stories.”