Historic preservationists, architectural historians and conservators have wide-ranging responsibilities. From extensive and intensive research, to detailed and technical writing, and the creation of innovative programming for both the youth and adult members of our community, the Heritage Foundation preservation and education team tackles an ever-changing array of day-to-day and week-to-week tasks.

However, one of our favorite opportunities is fieldwork, especially architectural and cultural fieldwork. So, what is fieldwork and how and why do we use it in our work at the Heritage Foundation?

Image of the front façade of the Perkins-Winstead-Jewell-O’More house, November 2020. Courtesy of the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County

The biggest preservation endeavor to date for the Heritage Foundation is the currently underway Franklin Grove Estate & Gardens project and has presented the preservation team with an amazing fieldwork opportunity. This historic property was once two properties, owned originally by the Perkins and Hines-McNutt families. Following the Civil War, the properties were sold. The most notable historic home at Franklin Grove is the Italianate-designed Winstead House (originally built for William O’Neal Perkins; most recently, home to the O’More College of Design, and soon to be the Moore Museum of Art)

The other is the Haynes-Berry house, situated practically on top of where the antebellum Hines-McNutt house once stood. We know from research that there were multiple owners and multiple outbuildings that existed on the property, but to understand what is still here and what is no longer, we need to studiously collect more information.

While thorough accounts of the properties are rare, two detailed accounts left by Sallie Hines-McNutt and the Reverend Edwin H. Freeman, give us a peek into the past. Sallie McNutt discussed Federal occupation and the dismantling of her family’s outbuildings including barns, enslaved dwellings, smokehouses, and the destruction of their front yard, side yard, gardens, and groves.

The McNutt family, removed from their property in May 1863 by the Federal army, opened their property to becoming an African American refugee center and an army field hospital. The property witnessed two battles including the famed battle of November 30, 1864.

Image of the front façade of the Haynes-Berry House, c1889. This area was once owned by the Hines-McNutt family whose Greek Revival house stood in the vicinity of where the Haynes-Berry house stands today. The visible stone foundation may hold clues to the Hines-McNutt outbuildings on the property.

Courtesy of the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County

Reverend Freeman, a free-born African American pastor and educator with the American Missionary Association wrote in June 1866, “…we adapted a Freeman School, about a quarter mile southeast of Franklin, on an elevated spot, in Midway of the battlefield, stand the building we now occupy. This building before the war was one of the largest and finest that could be found in this part of the state, – its surroundings were lofty trees of elm and Poplar, beautiful flowers or almost every description, extensive and well laid-out gravel walks…but God design was to change all of this…to have it occupied for a Freedman School…the following statement shows that it has been well occupied with 330 different pupils…and the daily night average including night school has been over one hundred-fifty.”1

Analyzing their accounts allows us to ask the hard questions that shape our investigative work on how best to preserve, interpret and share the history of Franklin Grove.

As we begin to analyze and use the archaeological data recently collected by TRC, Inc., a cultural resource management firm, we will get a better sense of building size, materials, and foundations that may remain beneath the surface. We hope to learn about a building’s use and any material culture associated with each space. The mid-19th century horseshoe, pottery, and wrought iron nails unearthed during our team’s initial survey has been helpful in revealing cultural changes associated with the property.

Image of 19th century horseshoe, possibly from the Civil War, as well as stamped brick and a piece of handmade pottery are all clues as to the people and events that shaped Franklin Grove. Image courtesy of the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County

Despite having a wealth of information, questions remain that need answers before the rehabilitation of the property can take shape. While we are only in phase one of a multi-phased approach to capturing archaeological data, one of our goals is to get a better sense of what buildings may have been on the property, including building size, materials, and foundations. This is where are fieldwork comes in. Fieldwork is a hands-on research approach to a specific site, relevant to posed research questions.

Our fieldwork objective at Franklin Grove, is to collect as much useful information as possible, while examining the architecture and the cultural landscape of the entire property. For our preservation team, this means examining not only buildings but studying similar buildings in the area that still have existing outbuildings. Over the past several months, we visited several local sites to better understand local building types from the antebellum period through the early 20th century, to help inform our design decisions for Franklin Grove.

Images of GPR (ground penetrating radar) being performed by geoscientists and archaeologists with TRC, Inc at Franklin Grove, November 2020. Courtesy of the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County

Image of Blake Wintory and Architectural Historian and PhD Graduate Research Assistant with the Center for Historic Preservation Amanda Hamilton examining the historic stone walls along Lewisburg Pike, the east boundary of Franklin Grove that leads to the Berry Circle neighborhood. Image courtesy of the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County.

So, what does fieldwork look like and how long does it take? At Franklin Grove, we spend a few days each week working on our continued investigations, architectural assessment, paint, and wallpaper analyses, and planning for the relocation and rehabilitation of the Lee-Buckner Rosenwald School.

First, all fieldwork begins with research. Hours of research are conducted at archives, in person or online, to locate the most historically, geographically, and architecturally relevant examples pertaining to the project. As part of our professional services, we offer any historic property owner(s) an opportunity to work directly with our preservation team.

In those specific cases, our fieldwork is tailored to meet the historic property owner(s) needs, which include building a relationship, clearly stating our desire to assist them in understanding how best to preserve or rehabilitate their property and sharing our findings with them.

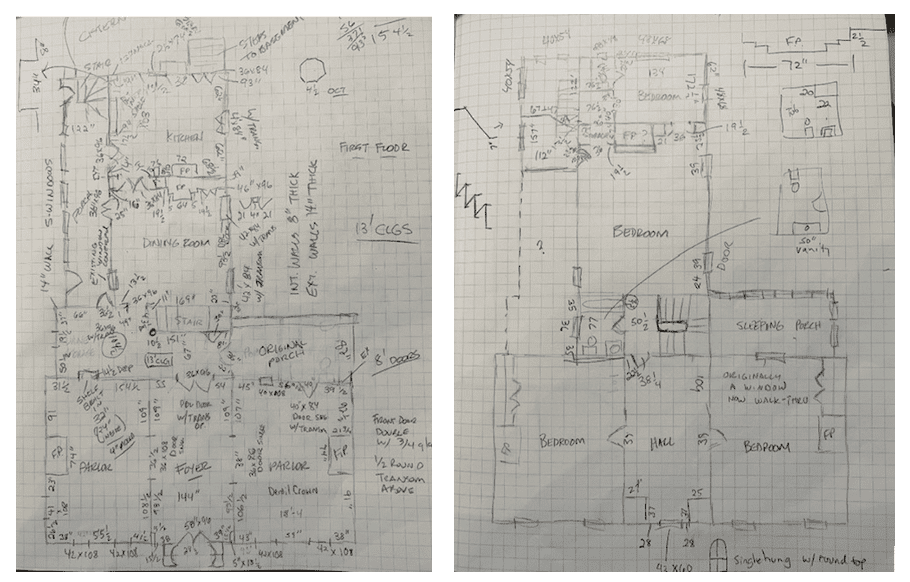

Original architectural measured drawings of the Perkins-Winstead-Jewell-O’More house, by Amanda Hamilton, architectural historian and PhD student, Graduate Research Assistant with the Center for Historic Preservation at Middle Tennessee State University, July 2020. Courtesy of Amanda Hamilton.

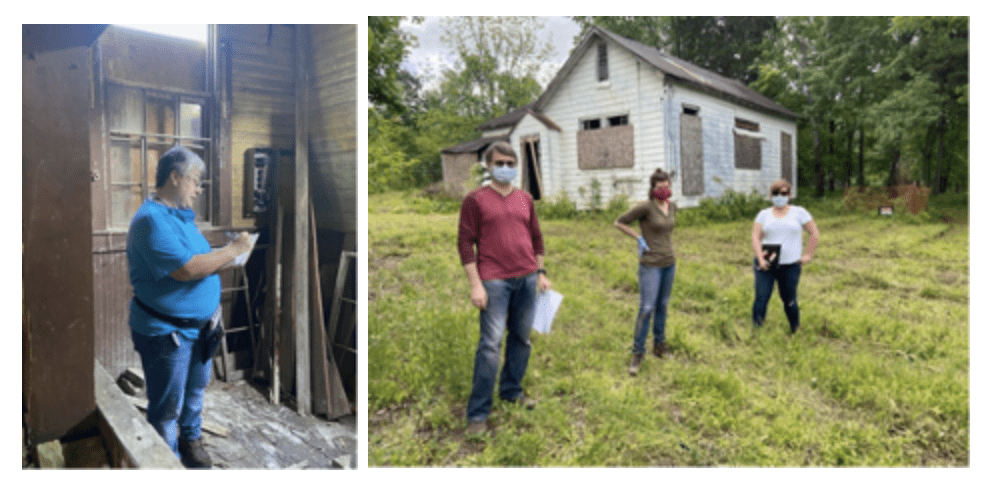

Image of Heritage Foundation’s Preservation Team conducting fieldwork at the Lee-Buckner Rosenwald School, Summer 2020. Image (left) Amanda Hamilton taking notes while measuring the industrial room in the school. Image (right) Director of Preservation Dr. Blake Wintory, Architectural Conservator Grace Abernethy, and Senior Director of Preservation Rachael Finch, standing in front of Lee-Buckner, the only remaining Rosenwald in Williamson County. Images courtesy of the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County.

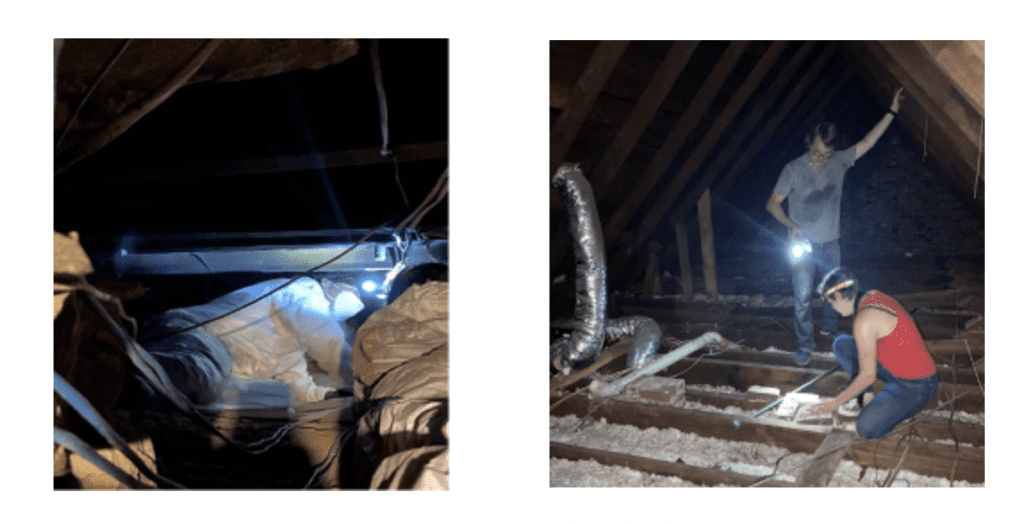

Having appropriate equipment is a necessity. Whether at Franklin Grove, or a private property owner’s site, we must be well prepared. Our equipment consists of multiple cameras, flashlights, headlamps (for crawling in tight attic and basement spaces,) measuring tapes, pencils, and notebooks. When we first began our fieldwork at Franklin Grove, we walked through the entire property and took a general survey. Many photographs were taken. Conducting fieldwork with a team is ideal.

Image of Heritage Foundation’s Preservation Team conducting fieldwork at the Lee-Buckner Rosenwald School, Summer 2020. Image (left) Amanda Hamilton taking notes while measuring the industrial room in the school. Image (right) Director of Preservation Dr. Blake Wintory, Architectural Conservator Grace Abernethy, and Senior Director of Preservation Rachael Finch, standing in front of Lee-Buckner, the only remaining Rosenwald in Williamson County. Images courtesy of the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County.

Image (left) our preservation team in the basement and crawl space of the original c1855 Perkins house. Hazmat suits, N95 masks and headlamps are all necessary to conduct safe and in-depth fieldwork. The despite fire damage during the war, our team discovered the antebellum bell system fully intact. Image (right) Director of Preservation Dr. Blake Wintory and Architectural Conservator Grace Abernethy use high powered flashlights and headlamps to view the construction methods and materials used within the attic space of the c1889 Haynes-Berry house, June 2020. Images courtesy of the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County

After our initial walk through at Franklin Grove, our team split up the assigned tasks. One person took measurements and drawings of the entire Perkins-Winstead-Jewell-O’More house. Another led paint and wallpaper analysis. Another took on the architectural assessment, taking precise images of its interior and exterior, as well as any additional photographs needed of the property.

Another led the environmental and cultural assessment of the property, documenting placement of outbuildings, gardens, trees, modern day drives, pathways, and modern-day exterior lighting. All team members take notes and collaborate on overall assessments, particularly as it pertains to the entire property’s rehabilitation and interpretive planning.

While many of our processes are the same when we visit a privately owned historic property, there are a few differences. We speak directly to the property owner and set a time to come out for a visit. Many property owner(s) collect a wealth of information on their own and enjoy being as involved as possible in the process with us. While we walk their property, we continue to ask questions of the property owner(s) and take notes. Often, the property owner(s) will share anecdotal information that is valuable for our fieldwork purposes.

Image (left) Architectural Conservator Grace Abernethy taking paint samples from the ceiling medallion in the center hall of the Perkins-Winstead-Jewell-O’More house. Image (left) Director of Preservation Dr. Blake Wintory examining the trees and landscape of the back property at Franklin Grove. Images courtesy of the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County

Image (left) Dr. Blake Wintory removing dead tree limbs from the historic serpentine wall. Removing falling limbs from historic stone walls protects the walls from additional deterioration. Image (right) Heritage Foundation’s Preservation team surveying the historic serpentine wall and surroudning grounds near South Margin and Lewisburg Pike. Courtesy of the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County

Fieldwork visits to the Parham School in southwestern Williamson County. We enjoyed visiting with the property owner and learning about his experiences and research on this c1911 rural school. Image (left) Dr. Blake Wintory taking notes on the school’s interior. Image (right) Our preservation team discussing the property owner’s places to fully restore the school. As a part of our professional services, we are writing the Parham School’s National Register Nomination. Images courtesy of the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County

Franklin Grove’s fieldwork is ongoing and there is plenty of information to disseminate. We scan and save all our notes along with all drawings. We digitize and organize our photographs for easy reference. For site visits to private historic properties, we follow the same methodology, however; we will share our field notes and findings with property owner(s).

We thank them for allowing us access their property, and if warranted, offer to prepare a brief preservation plan or historic conditions assessment, as part of our professional services that provides preservation scholarship and up to date relevant historic records. For Franklin Grove, our fieldwork will yield an in-depth historic structure report that will serve as the roadmap for ongoing and future planning.

Fieldwork allows us to envision what the buildings on the property may have looked like in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It allows us to see into the past as we crawl through “hidden” spaces, covered by modernization. As we look at examples from similar periods of significance in the county, we begin to see patterns. These building and landscape pattern can confirm or challenge our hypotheses.

Fieldwork takes dedicated time to ensure the rehabilitation or restoration of a historic property is completed as accurately as possible. For Franklin Grove, we hope by rehabilitating its buildings and grounds to a prominent level of detail, we may provide future visitors with the most authentic experience as possible. For our county’s private historic property owners, we hope to build lasting relationships so we may continue to inform and instill best practices of preservation for generations to come.

Get Involved!

If you own a historic property, and like our preservation team to visit your property, please contact us at info@williamsonheritage.org.

If you would like to learn more about the ongoing preservation efforts at Franklin Grove, please visit http://www.williamsonheritage.org/franklingrovehistory.

To contribute to our annual fund to keep preservation of our historic and cultural resources going, please go to www.williamsonheritage/donate.

To consider making a leadership gift to the Franklin Grove Estate & Gardens project or its endowment, please contact CEO Bari Beasley at bbeasley@williamsonheritage.org.

Endnote:

[1] Letter dated June 28, 1866, from Reverend Edwin H. Freeman stationed in Franklin, Tennessee, to the Superintendent of Education for the American Missionary Association, Reverend Samuel Hunt, in New York City, New York. MF: 364, American Missionary Association records, 1836-1905, Tennessee State Library and Archives. Originals are held by the Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana.