Blake Wintory, Ph.D.

Director of Preservation and Education

Heritage Foundation of Williamson County

Female Education in the 19th Century

The Heritage Foundation’s Franklin Grove Estate & Gardens derives its name from The Female Seminary of the Franklin Grove, a secondary school founded on the grounds by the Rev. Canelm H. Hines and his wife Sarah around 1832. The Female Seminary was part of a wave of female academies that spread across the South as communities and families demanded education beyond the primary level for their daughters, sisters, and nieces.

Female academies provided an intellectual education for girls ages 12 to 18, similar to the curriculum at male schools. A generation or two before, schools for girls limited education to domestic tasks and ornamental subjects like sewing, needlework, music, and crafts. The female academy movement placed intellectual subjects at the forefront of girls’ education while keeping ornamentals as electives. However, in the agrarian South, there was little expectation that girls would work outside the home upon graduation. According to historian Christie Anne Farnham in her book, The Education of the Southern Belle: Higher Education and Student Socialization in the Antebellum South, southern education at a female academy was ultimately domestic; turning young women (“belles”) into respectable ladies, wives, and mothers1

With Tennessee’s public or common schools woefully underfunded, only the wealthiest families could afford to educate their daughters. Elite private academies charged up to $200 per year with board, making education a luxury available only to the daughters of planters, urban businessmen, and professional clergy.

Wealthy slaveholding counties like Williamson were fertile ground for female academies. Between 1822 and 1861, at least 22 female academies emerged across the county.2 While many were short-lived, the impact of these schools is apparent in women’s literacy. In 1850, Tennessee’s agrarian economy and rudimentary common schools resulted in a 47.4% literacy rate for white women, but in Williamson County, 82.1% of white women were literate.3

The Female Seminary at Franklin Grove

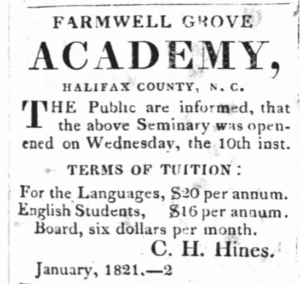

In the early 1820s, C. H. and Sarah Hines operated the Farmwell Grove Academy and a girls’ school in Halifax County, North Carolina. Newbern Sentinel, January 27, 1821.

Canelm H. Hines and Sarah Anthony, born in North Carolina around 1786 and 1792, married in 1816 in Craven County, North Carolina. Ordained in the Methodist Episcopal Church, Rev. Hines preached on the Raleigh circuit as early as 1811.4 By the early 1820s, the couple resided in Halifax County, North Carolina. There, Rev. Hines operated the Farmwell Grove Academy, and Mrs. Hines ran the eponymous Female School.5

In 1829, the 43 year-old and 37 year-old couple moved west, settling outside of Franklin, Williamson County, Tennessee on 30 acres on the Big Harpeth River with their two daughters, Lucillo, 11, and Catherine, 9.6 The Hines likely traveled with enslaved black laborers as they were the owners of 13 men and women, according to the 1830 Census. The enslaved laborers constructed the two-story, Federal-style brick home that would house the family and school. By 1870, the home would resemble Randal McGavock’s nearby Carnton.7

The Hines-McNutt home, pictured here around 1870 when it served as a boys’ school, was originally built around 1830 as both the home of C. H. and Sarah Hines and the location of the Female Seminary. The home was torn down around 1898, when the Haynes-Berry House was constructed. Photo courtesy of Rick Warwick.

The couple, members of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, soon organized the Female Seminary.8 While the school was not owned by the church, it was likely affiliated with St. Paul’s. It took the name “seminary” rather than “academy” to emphasize a higher quality education and a higher connection. An affiliation with St. Paul’s provided a ready pool of students and patrons for the school and kept Episcopal girls in the faith and out of rival denominations.

While we know about the Female Seminary of Franklin Grove, only a few primary sources have emerged: a handful of advertisements, a single family history, and an 1841 receipt.

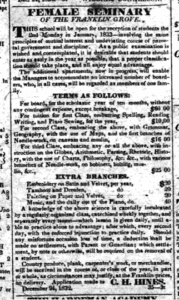

The earliest known source is an advertisement in the Western Weekly Review, January 25, 1833. The advertisement announced the reception of students under the “principles of mutual interest and undeviating course of parental government and discipline.” The Hines anticipated “an increased number of boarders, who…will be regarded as members of the family.”

This 1833 advertisement is the earliest known mention of the Female Seminary of the Franklin Grove. Western Weekly Review, January 25, 1833.

Boarding ran $60 for the ten-month term and increased with academic classes and ornamental subjects. Parents or guardians of a third class student could expect a tuition bill of up to $185. In lieu of cash, the account could be settled with “country produce, plank [building timber], carpenter’s work, or merchandise.”9

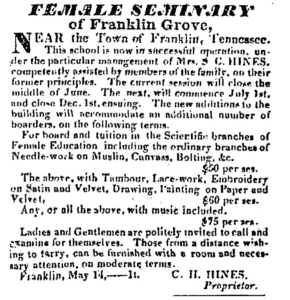

Notifying the readers of the Nashville Republican in 1834, C. H. Hines wrote the school was “under the particular management of Mrs. S. C. HINES [and] competently assisted by members of the family, on their former principles.”10 Mrs. Hines, whose oldest daughter was 15 in 1834, presumably taught most of the courses. She was later assisted by Elizabeth Balch and Pamelia Noble.11 Students’ knowledge, Hines explained, is “carefully inculcated by a regularly organized class, catechised weekly together,” daily individual lessons, and “with enforced injunction to practice daily” “every second day.” The first class consisted of spelling, reading, writing, and plain sewing; second class included grammar, geography, and needlework; third class instructed on globes, arithmetic, parsing, rhetoric, history, charts, philosophy, and needlework. Ornamentals included embroidery on satin and velvet; tambour and dresden; painting on paper and velvet; and music, including “the daily use of the piano.”12

This 1834 advertisement announced Mrs. S. C. Hines as head of the Female Seminary. Nashville Republican, May 13, 1834.

A 1922 family history, compiled by Lucy Henderson Horton, offers a glimpse of education at the Female Seminary. Sisters Mary and Rachel Hughes, born in Virginia in 1816 and 1818, were school-age in 1828 when they arrived in Williamson County. That same year they attended the Harpeth Union Female Academy at Triune and later attended the Hines’ Female Seminary. The history emphasizes the ornamental subjects—“music and art”–with memories of the “old-fashioned piano,” still in the family, with “carved mahogany legs” and simplistic yet “tasteful” paintings. Some of the other relics hint at their intellectual education: cards of merit for parsing and penmanship and an essay on gratitude by Rachel. The essay, the author confirmed, proved Rachel “to have been a girl of high ideals.”13

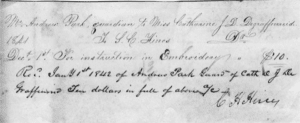

Further details about the Female Seminary can be found in the 1840 Manuscript U.S. Census. From this source, we learn the Hines household supported a school with 22 scholars and one teacher; we can further deduce the Hines family boarded four girls between the ages of 15-20.14 That detail suggests most students lived with family near or in Franklin–including Catherine DeGraffenreid, whose guardian, Andrew Park, paid the Hines $10 for “instruction in Embroidery” in December 1841.15

This receipt for instruction in embroidery from Andrew Park to C.H. Hines, December 1, 1841, is one of the few surviving documents related to the Female Seminary. Original in possession of Rick Warwick.

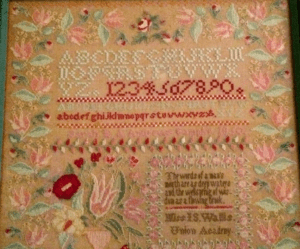

Samplers like this 1850 example by Sarah Andrews, who studied at Union Academy in Williamson County under Miss I. W. Wallis, show the embroidery and sewing skills girls learned in their ornamental classes. Unfortunately, no samplers have been found connected to the Hines’ Female Seminary. Courtesy of Rick Warwick.

A decade later, in 1850, the census showed two possible students boarding with the Hines family: Ellen McGavock, 18; Josephine Southall, 12. Their presence shows a growing connection to the McGavock family. Jane Ellen McGavock was daughter of Randal and Almira McGavock who lived near Nashville and owned a sugar plantation in Louisiana. A close relative, Josephine P. Southall, the daughter of Joseph Branch and Mary Cloyd (McGavock) Southall was another McGavock relative.16 Four years later, Sallie Hines, the youngest Hines daughter, married James A. McNutt, the grandson of Hugh McGavock.17

Franklin Female Institute

However, it is more likely McGavock and Southall were students at the Franklin Female Institute at Five Points and not the Hines’ Female Seminary. The Female Institute, founded and chartered by Tennessee in 1847, likely had eclipsed the smaller Female Seminary. This might also explain a comment by Sarah Hines in the only known letter written by her. Mrs. Hines, writing to John Noble in May 1848, revealed the family was recovering from an an “ordeal…[of] missplaced confidence & false friendship.”18 Founders of the Franklin Female Institute included friends and neighbors like William O’Neal Perkins, James R. McGavock, and John H. Otey.19

The 1850 Census seems to confirm the Female Seminary had closed. The Social Statistics schedule recorded nine academies or other schools with 20 teachers and 475 students. Individual schools are not identified; however, only one female academy is accounted for. Supporting four teachers and 100 students, this school is no doubt the Franklin Female Institute.20

By 1860, Canelm Hines, age 74, was living in Nashville and Sarah is believed to have recently died. His daughter, Sallie and her husband James McNutt lived at Franklin Grove. James’ position as principal at the Franklin Female Institute also points to the fact that the Female Seminary had closed.21

Freedmen’s Bureau School & Buena Vista Boys’ School

The Civil War and occupation of Franklin in 1862 by Union Troops would change everything at Franklin Grove. Refusing to profess loyalty to the Union, the McNutts fled to Max Meadows, Virginia. When they returned to Franklin in 1866, they found their home was again being used for education. A freedmen’s school, educating former slaves who had been denied an education before the war, rented a room for perhaps a few months in 1866. This change was short-lived. The McNutts took possession of their home in the summer of 1866 and established a boys’ school called Buena Vista, forcing out the freedmen’s school.22

Franklin Grove has a rich history that connects to the beginning of Franklin and Williamson County. The story of the Hines family and the Female Seminary and the two nineteenth century schools that followed tell us a great deal about western migration, the role of women and education in the development of the town and the county. Research at the Heritage Foundation will continue as we preserve and discover the history of the place we call Franklin Grove Estate & Gardens.

Endnotes:

- See Lisa Tolbert, “Commercial Blocks and Female College: The Small-Town Business of Education Ladies,” in Shaping Communities: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture VI, eds. Carter L. Hudgins, and Elizabeth Collins Cromley (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1997): 204-215.

- Historian Jeri Hasselbring estimated twenty-two female academies and one female college in Williamson County based on her examination of newspaper advertisements and other sources. See, Jeri Hasselbring, “Female Education in Antebellum Williamson County: 1822-1861,” Williamson County Historical Society Journal (1997): 9-24. Two other scholars, Jennifer C. Core and Janet S. Hasson, believe Williamson County has the “most of any county in the state.” See Core and Hasson, “Female Education and the Ornamental Arts in Antebellum Tennessee, Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts vol. 40 (2019), accessed online https://www.mesdajournal.org/2019/female-education-and-the-ornamental-arts-in-antebellum-tennessee/.

- Literacy rates were calculated from The Seventh Census of the United States: 1850 (Washington: Robert Armstrong: 1853). Compare with George C. Rable, Civil Wars: Women and the Crisis of Southern Nationalism (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1989), 18. On common schools, see A. P. Whitaker, “The Public School System of Tennessee, 1834-1860,” Tennessee Historical Magazine (March 1916): 1-30.

- North Carolina County Registers of Deeds. Microfilm. Record Group 048. North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC. Accessed on Ancestry.com. “North Carolina, County Marriages, 1762-1979,” North Carolina State Archives Division of Archives and History; FHL microfilm. Accessed on https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QP9R-387Q. Rev. John Paris, History of the Methodist Protestant Church…Account of Transactions in North Carolina (Baltimore: Sherwood & Co, 1849), 56-57, 61, 65, 206. “Wendell United Methodist Church: Our History, 1903-2003,” accessed via internet, https://nccumc.org/history/files/Wendell-UMC-History.pdf; Mary Louise Butler Edwards, Salem, A Goodly Heritage, 1848-1976: The History of Salem United Methodist Church, accessed via Archive.org https://archive.org/details/salemgoodlyherit01edwa.

- Newbern Sentinel, January 27, 1821; Jerry L. Cross, An Overview of Schools, Academies, and Efforts to Promote Education in Halifax County, North Carolina, 1790-1840, report submitted to North Carolina Division of Archives and History, 1987, accessed on North Carolina Digital Collections, https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p16062coll6/id/11355/rec/14.

- Deed Book K, pg 14. Ages of the daughters are calculated from 1850 Census, Williamson County, Tennessee.

- 1830, 1850 U.S. Census, Williamson County, Tennessee. See Virginia Bowman and Louise Lynch,“Records open window on Carnton mystery,” The Review-Appeal, August 24, 1987. A ca. 1870 photo, published with the article, comments on the architectural resemblance.

- St. Paul’s Episcopal Church Records, Williamson County Archives. Records include the recorded baptisms of five of the Hines’ servants [slaves] in 1848. It is not clear why the Hines switched from the Methodist Episcopal Church to the Episcopal Church.

- Western Weekly Review, January 25, 1833.

- See Nashville Republican, May 13, 1834, June 21, 1834, December 16, 1834.

- Balch and Noble are mentioned without any detail in Bowman and Lynch, “Records open window on Carnton mystery,” The Review-Appeal, August 24, 1987. Little is known about Balch, but Noble was a New Hampshire-born relative of the Hines. She likely arrived in Franklin in late 1840. See “Letters of Pamelia Noble Carothers to her brothers, John Harrison Noble (1857-1865)” in Williamson County & the Civil War- As Seen Through the Female Experience 2008. Earlier letters, dating to as early as October 1840, are not printed, however transcriptions are in the possession of Rick Warwick, editor of the series. In 1843, she married a local widower, James Carothers, and presumably stopped teaching that year. See Tennessee State Marriages, 1780-2002, accessed on ancestry.com.

- Western Weekly Review, January 25, 1833.

- Lucy Henderson Horton, comp. Family History (Franklin, Tenn.: Press of the News, 1922), 47-48.

- The 1840 manuscript census lists 23 people in the Hines household. Thirteen were enslaved, three were likely his daughters, his wife, possibly a son, and himself; leaving the four remaining girls as likely students. The one teacher is another indication that Pamelia Noble, age 29 (born in 1811), does not seem to be in the household.

- Receipt for instruction in Embroidery, Andrew Park to C.H. Hines, December 1, 1841. Original in possession of Rick Warwick.

- In addition to McGavock and Southall, the 1850 Census lists C. H Hines, a 64-year-old-farmer with $10,000 in real estate; Sarah C. Hines, 58; Lucillo [Lucy] Hines, 32; Sarah [Sallie], 19; and his married daughter’s family, John Saunders, 33, an Episcopal Minister; Catherine, 29; Matthew, 5; Lucilla, 1. Gray, Robert, The McGavock Family: A Genealogical History of James McGavock and His Descendants from 1760-1903 (Richmond, VA: Wm Ellis Jones, 1903), 29, 34, accessed via Google Books https://books.google.com/books?id=lZ-4NiAVK-gC&source=gbs_navlinks_s

- Bowman and Lynch, “Records open window on Carnton mystery,” The Review-Appeal, August 24, 1987.

- Sarah C. Hines to Mr. John H. Noble, May 19, 1848, transcribed letter in possession of Rick Warwick.

- See “An Act to incorporate the Franklin Female Institute in the county of Williamson,” in Acts of the State of Tennessee Passed at the First Session of the Twenty-Seventh General Assembly, 1847-8 (Jackson, Tenn.: Gates & Parker, 1848), 80-81 accessed on Google Books https://books.google.com/books?id=5sk4AAAAIAAJ&lpg=PA80&ots.

- See Appendix in The Seventh Census of the United States: 1850, accessed https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1850/1850a/1850a-49.pdf?#.

21. U.S. Census Davisonson County; Williamson County; Nashville Union and American, August 12, 1860.

- “United States, Freedmen’s Bureau, Records of the Assistant Commissioner, 1865-1872,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9TD-L8ZX?cc=2427901&wc=73RQ-39S%3A1513853902%2C1513923485: accessed 27 November 2018), Tennessee > Roll 26, Records relating to abandoned property, registers of abandoned property, vol 1-3, Feb 1861-May 1868 > image 234 of 282; citing multiple NARA microfilm publications; Records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1861 – 1880, RG 10; “Tennessee, Freedmen’s Bureau Field Office Records, 1865-1872.” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9GF-5H76?cc=2333777&wc=3M5J-PTL%3A1555882802%2C1555883901: 27 February 2015), Assistant Commissioner > Roll 44 (T142), Relating to the restoration of property, D-K, 1865-1868 > image 233 of 1337; citing NARA microfilm publication M1911 and T142 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

Selected Sources:

1830, 1840, 1850, 1860 U.S. Manuscript Census, accessed on familysearch.org and ancestry.com.

Bowman, Virginia and Louise Lynch, “Records open window on Carnton mystery,” The Review-Appeal, August 24, 1987.

Jennifer C. Core and Janet S. Hasson, “Female Education and the Ornamental Arts in Antebellum Tennessee, Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts (2019), accessed online https://www.mesdajournal.org/2019/female-education-and-the-ornamental-arts-in-antebellum-tennessee/

Corlew, Robert E. Tennessee: A Short History, Updated 2nd edition. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1990.

Farnham, Christie Anne. The Education of the Southern Belle: Higher Education and Student Socialization in the Antebellum South. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1995.

Hasselbring, Jeri. “Female Education in Antebellum Williamson County: 1822-1861,” Williamson County Historical Society Journal (1997): 9-24

Horton, Lucy Henderson, comp. Family History. Franklin, Tenn.: Press of the News, 1922. Accessed on Google Books https://books.google.com/books?id=hWtVAAAAMAAJ&.

Nashville Republican, May 13, June 21, December 16, 1834.

Nashville Union and American, August 12, 1860, accessed at newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/image/87856895/.

Newbern Sentinel, January 27, 1821, accessed on newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/image/55029987.

Nonpopulation Census Schedules for Tennessee, 1850-1880, accessed on ancestry.com.

Ott, Victoria. Confederate Daughters: Coming of Age During the Civil War. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2008.

Rable, George C. Civil War: Women and the Crisis of Southern Nationalism. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

Tolbert, Lisa. “Commercial Blocks and Female College: The Small-Town Business of Education Ladies,” in Shaping Communities: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture VI, eds. Carter L. Hudgins, and Elizabeth Collins Cromley. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1997, 204-215.

Western Weekly Review (Franklin, TN), January 25, 1833.

Whitaker, A. P., “The Public School System of Tennessee, 1834-1860,” Tennessee Historical Magazine (March 1916): 1-30.